A Brief Portrait of Lowell Labor

I began writing this as a quick summary for my partner who was unable to attend the Lowell Labor walk this past Labor Day weekend. But as I started writing, I figured I’d share it with you guys as well.

The tour began in between Lowell Telemedia Center and the National Park’s visitor center with a healthy crowd of attendees, a good mix of locals and out-of-towners. Our tour guide was Professor Bob Forrant, a history professor at UMass Lowell and a former machinist. The majority of the information provided is recounted from notes taken during the tour. I’ve tried to clear up any ambiguity in my notes with supplementary reading and have sprinkled in some details I’ve learned when corroborating my notes. Shoot me a message if you notice any historical incongruities, and I encourage readers of this article to attend future walks or check out Professor Forrant’s show History in Lowell on the LTC Youtube page to learn more. Now let us continue with the tour.

There’s A Lot To Plan About Lowell

Lowell is unlike many of the towns that first sprang up in New England as it was planned and willed into existence. Investors associated with the Boston area, aptly named the Boston Associates were excited by the new mechanized tools for processing the cotton harvested by enslaved people in the South. The first test was in Waltham, using the plans from English mills stolen by Francis Cabot Lowell.

After seeing the success of the Waltham-system, the Boston Associates sought to reproduce and scale up production at the confluence of the Merrimack and Concord river. A place known for its excellent fishing and strong current among the indigenous tribes.

In order to process the land, the investors would need to divert the powerful current into controlled canals that would be funneled into mills that had yet to be built to power machines whose operators were not quite known yet. This would require a great deal of labor to perform, ideally cheap labor.

The Intent to Move Massive Rocks

Our first stop was right across from Market St. at The Worker, a statue of a canal worker in a fountain using his mortal strength to pry and position the great stones that line the canals through which water power was harnessed for the mills. The Worker’s depiction is reminiscent of war-time posters of men and women staring chin-up into the distance with their shoulders borne broad and without a flicker of doubt. I imagine for the average worker, this would not be the typical posture maintained. Perhaps in the beginning of the day, sure, but certainly not at the end.

Irish labor was essential for industrializing Lowell and setting the stage for the mills. By diverting water from the river and controlling its distribution to the mills, water power could be sold to operate the heavy machinery. But creating the channels for this power was extremely dangerous work.

There were a variety of ingenious and imperfect methods for performing this labor. Horses and oxen, mostly oxen, were sometimes used to subsidize manpower and crank large gears about to hoist rocks from the ditches. Other times these rocks had to be dynamited, which may have played upon the nerves considering the fact that it was never quite obvious how much dynamite was too much dynamite.

And when those stones were blown up into somewhat more manageable sizes, another method for displacing them was to connect to the swinging end of a device commonly referred to as a catapult and launch that sucker into kingdom come. Similar with dynamite, you can only ever approximately know what you’re doing so you may find headlines in the local paper exclaiming that a boulder has landed on your neighbors house, which is a mildly amusing statement to read. Less amusing were the instances in which the boulder would fly straight up and fall straight down, crushing the workers below.

Mechanics and Fugitive Slaves

Across from the nearby canal was the Mechanics Hall operated by the Middlesex Mechanics Association. Professor Forrant referred to this as the Silicon Valley of Lowell for at the time, it was a leading example of the technological advances made eat the time, equipped with an impressive library that has since been donated to the Pollard Library and various training programs to ensure that workers were trained to be as skillful as required to perform the tasks asked of them.

Lowell was also one of the nodes that comprised the underground railroad. Fugitive slaves would inhabit and work the storefronts below as abolitionists and women suffragists met above. In the meantime, the industrialists continued to industrialize.

A Promise for Young Women

After the mills were built, a workforce was needed to actually operate the looms and various machines installed across the acres of floor space within the mills. One of the notables aspects of the industrial revolution was its ability to bring women and children into the industrial workforce, where before their primary labor was focused on domesticity. Now mill representatives were going out to appeal to the heads of households to lend them their daughters to process cotton into cloth.

In exchange for the labor of their daughters, they would receive room and board, attend church and be able to make money, effectively generating their own dowry for when they were married to the guy down the road. From the perspective of the prospective laborer, there would be the chance to go into the city, embark on some adventure and earn her own living.

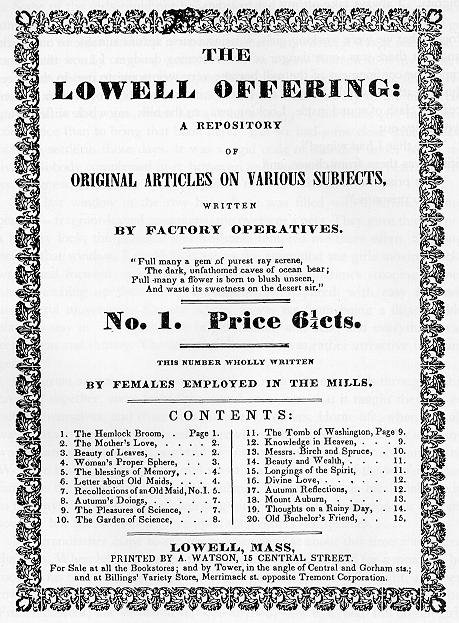

The reality was much more banal and arduous. The early morning bell signaled the start of the day and the young women of Lowell would labor for twelve to thirteen hours awaiting the sounds of subsequent bells to break up the day. Some women would pass the time by pasting broadsides to their looms that they could read while they worked, stealing back moments of their time. Other women wrote themselves, circulating original pieces in the mill magazine The Offering which often celebrated the work ethic, the resolve and the scale of production in the mills. Others would contribute to the Voice of Industry, offering more critical accounts of their day-to-day lives. Limbs pulled into the spinning machinery, the heat and agitation of the thick cotton fiber air, and of course, as any dutiful mill tour attendee would recount, the occasional accidental on-site scalping that occurred.

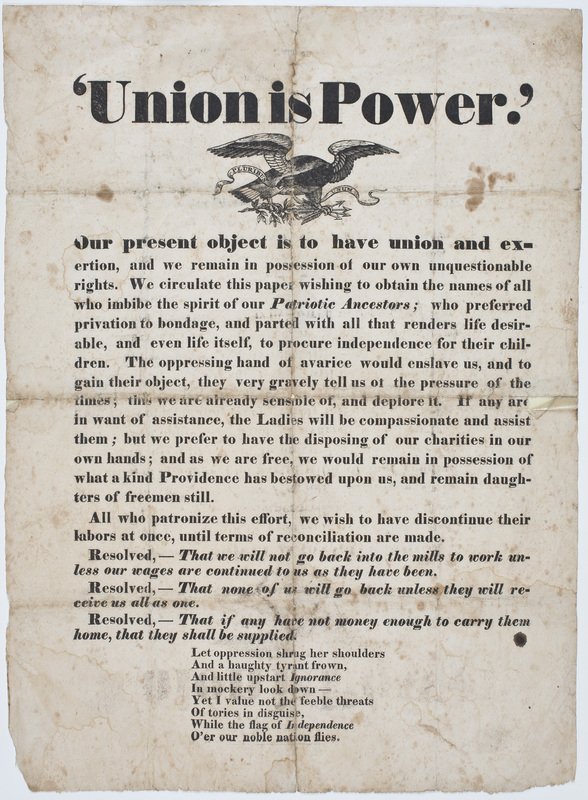

This was before the labor movement and despite the mechanics hall there were no clear levers or pulleys to improve working conditions. Between the canal-workers and the mill girls, enough injuries accrued to warrant setting up a hospital, but this likely stemmed from a sheer maintenance standpoint rather than one of simple compassion. So our fore-sisters did what they needed to. They formed a strike, and created a disruptive ripple that continues to be felt today.

Lowell is a Union Town

The mills eventually pivoted and shifted their workforce to utilize the labor of new immigrant groups, typically exploiting language barriers to play off each other and keep wages low. It seems to me, this is where much of the “they’re taking my jobs” rhetoric stems from. But as the tactics of management evolved, so too did the tactics of laborers and labor organizers.

Lawrence provides a gleaming example of this with their iconic Bread and Roses strike, which I might do a write-up on next. In the interest of leaving some space for that, I’ll avoid going into great detail, but suffice to say, immigrant groups were able to overcome linguistic divisions through a developed relay network featuring bilingual workers that acted as fact-checkers and translators. In Lowell as well, language was celebrated among the workers as marching bands paraded down the streets singing songs in each others languages. Did the Portuguese worker understand each word of the Polish tune? Likely not. But in terms of struggle and environmental pressures, they indeed spoke the same language.

As Belvidere is the wealthiest neighborhood today, it was then as well. Professor Forrant recalls a newspaper with the headline that read “Workers Invade Belvidere,” as droves of people sang and danced in the street. These marches were meant to be festive and celebratory in nature as well as galvanizing, though there were sometimes arrests made including that of a young Greek girl who was lionized by the community becoming a symbol of resistance and solidarity.

In the 1880s and 1890s, there were somewhere around 25-30 unions, and by the 1920s there were nearly 70 unions. On middle street, across from The Old Court, there was a union meeting hall where workers would congregate and exchange pamphlets and and listen to speakers. Police officers would often go undercover to these spaces identifying sympathizers of the Russian Revolution or seeking sedition and traces treason in the folded pieces of paper being passed out.

Interestingly, the Boston police union had their own labor issues they sought resolution for. One of their qualms was that they felt like they shouldn’t have to pay for their own ammunition. Apparently, if they fired a round or two, it was expected that they would replace their own bullets. They attempted to organize, perhaps learning a thing or two from a confiscated pamphlet, however, most of the officers who went on strike permanently lost their jobs and were replaced by veterans of the first world war who already knew how to fire guns and were seeking avenues to reintegrate into society.

Red Scare Roundups

Continuing into the late 1910’s and early 1920’s, laws banning the critique of the U.S.’s involvement in the world war continued to be passed. It became illegal to disseminate radical writings through the postal system, and it was encouraged to inform the authorities if you felt your neighbor was ingesting any subversive ideas. In the large union hall on Middle St., forty people were arrested and taken to Deer Island where their politics were put on trial. One Lowell native was held there for two months.

Steel and coal strikes breakout among a larger pattern of labor upheavals. The work in Lowell is changing. Deindustrialization, which is thought of typically as being a relatively contemporary occurrence, is already happening as the mills shrink and smaller industries migrate into the city such as shoemaking shops. The Great Depression drives the union movement forward as workers become more desperate and have less to lose. The American Federation of Labor resists motions to unionize unskilled and migrant workers with brawls breaking out on their convention floors.

And as the economy dwindles and the strikes continue and the future seems less and less certain, thousands and thousands of people are trying to orient themselves in the seemingly most disorienting of times. Huge strong strikes form and a gun is procured.

It’s unclear whether this strike breaker knew or not that the strikers also had guns, but regardless, the popping of firearms was heard by the Bridge St. bridge as the police redirect traffic trying to avoid the shootout altogether. Eventually 400 workers are arrested. And in the background work continues to fluctuate and change, and many of the victories won by laborers eventually concede. These gothic industrial mills are emptied out and the work is relocated, globalized. And what happened in Lowell, Massachusetts now happens within large obelisk-like buildings in Southeast Asia or wherever the labor is cheapest.

And in those mills are young laborers deferring their education and pleasure to create products they cannot enjoy for the benefit of people they’ll never meet. And millions of college students enter into debt peonage that will last two thirds of their lifetime. And gaggles of people huddle round on Market St. to learn about the past during the last warm summer days.

History as it Relates to the Present Moment

What are we to take away from such accounts?

I suppose that depends on who you are. I presume a manager would wear quite a different lens than say a service worker, but I hope that both would see the humanity and the struggle of the people in these stories.

One dynamic I would highlight is the importance of advocacy for one’s self and others. The strength of developing and unifying community for a common cause. The reality of the power differential that continues to exist and the inherent potential violence of that power differential. I would point at the fact that the most interesting ideas come from the least expected places. I offer some small comfort to those struggling now, knowing that the struggle is shared and that change is possible. I would beg of the reader to challenge one’s imagination in envisioning the future and provide a gentle reminder that history is cyclical.

The labor movement won the weekend and forty hour work week, but now we must work two or three jobs to make ends meet. And how much of that money goes to paying rent that is often over a third or over half of one’s income.

The labor movement made unfair labor practices illegal, but they continue to exist and remain unreported and have been normalized in many work settings. An often times a complaint or even the mention of unionizing is considered grounds to be fired jeopardizing one’s livelihood.

The labor movement advocated for the rights of the working class, but many people working today don’t even see themselves as working class. Everyone’s a millionaire in the making waiting for that next lottery ticket.

But with the Hollywood strikes, and the UPS strikes, and the attempt at reforming railway work, the organizing of service workers, the protests and rallies of nurses, teachers, graduate students, RA’s and more, it’s difficult to argue we are in something of a moment ourselves. This very week the UAW is set to strike, which can lead to long awaited contract changes or the outsourcing of work in pursuit of cheaper labor. It seems like we ourselves are currently and actively becoming part of the history that has just been described. And if we acknowledge our roles as historical actors setting the stage for the next act, perhaps we’ll be mindful to use our time under the limelight well. And with a little bit of luck and solidarity, maybe we can tell a story that is wholly original.