The Panic Broadcast

This weekend, my partner and I are hosting a powerpoint party. I love a good powerpoint party because it’s the perfect premise to just let someone pop off on something they’re really passionate/enthusiastic about or to creatively interpret an open prompt. I’ve seen powerpoints on ghost real estate, the religious implications of the Bionicles franchise, cryptological languages, and cacti. This time the prompt is calling for Alien-themed presentations. So I thought I’d go back to a historical moment in American history that highly influenced my creative framework.

The Mercury Theatre

The Mercury Theatre was a creative project founded by Orson Welles and John Houseman in 1937 and blossomed from the Federal Theatre Project which was a program under FDR’s New Deal package wherein the United States provided public funding for the arts. And for those of you who are unfamiliar with Orson Welles, he is considered one of America’s great storytellers and charlatans, his most well-known work being Citizen Kane. He started out in theatre and then radio and eventually moved into cinema, and he often both produced and starred in any work with his name attached to it.

While I’m fixated on much of Welles’ body of work, I’m also well aware that he was very much a ham and an archetypical egomaniac, though an artist of great calibre all the same. Much of his work and many of his collaborations center him and his talent while often side-lining his collaborators and designers. I think this changed somewhat as he grew older and encountered a great many failures, but as we’re focusing on a single moment let us return to when he was twenty three years old, in the year of 1938, when The Mercury Theatre was producing a series of radio dramas.

Radio was still a new technology and only recently utilized by FDR as the first mass media tool through which he delivered his Fireside Chats. Oftentimes when a new media technology is invented the old forms are adapted, so theatre, literature and news were conventions that radio producers could look to adapt. Radio as a technology is unidirectional meaning there’s no feedback, you can’t tell who is listening and there’s no comments section or rewinding the program. Talkies, movies with sound, were popular by now, but the radio was ubiquitous and a perfect format to exploit the theatre of the imagination.

For The Mercury Theatre on the Air, Welles and his colleagues would take well-known books such as Treasure Island and Dracula and The Man Who Was Thursday and essentially rip them up and remix them into radio dramas. They’d perform these scripts live with a full band and foley artists for the sound effects and the 17th episode of the series was an adaptation of H.G. Welles War of the Worlds. It is famously remembered now as The Panic Broadcast.

The Panic Broadcast

The story goes like this.

At 8pm on October 30th, The Mercury Theatre went live with its Halloween production. f you tuned into CBS, you would hear this:

“The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in a radio play by Howard Koch suggested by the H.G. Wells Novel "The War of the Worlds." -War of the Worlds: Mercury Theatre on the Air (1938)

This was the clear introduction of the program as a work of fiction. However, you’re not going to catch that part if you were tuned into the much more popular variety show The Chase and Sanbourne Hour on NBC. At this moment there was a compelling ventriloquism act by Edgar Bergen who we’re all familiar with. Now I may not be very familiar with ventriloquism, but I always thought part of what made it interesting was seeing that the ventriloquist is not moving their mouth, though I suppose with radio you still don’t see their lips move so please disregard this thought.

Oh and in case you were wondering, War of the Worlds is a novel by H.G. Wells and if you haven’t read it, you may be in good company, it was suspected Orson hadn’t either. Earlier in production, the creative team was seeking a vessel to incorporate Breaking News conventions to create greater drama and urgency in the production. Welles and Houseman wanted to create an air of verisimilitude, of realism. So locations were changed to reflect American locations, and the names of real institutions were used in the first draft. CBS negotiated for about 28 name changes to avoid legal liability so for example, The United States Weather Bureau was changed to the Government Weather Bureau, Princeton University Observatory was changed to Princeton Observatory, and so on. Alright back to our regularly scheduled programming.

After the introductory announcement was made, the fiction began and reports started coming in regarding a meteorite that fell in Grover’s Mill New Jersey. A field reporter was sent out to investigate and send a remote transmission for the benefit of our listeners. The reporter checks in with his team to make sure that he’s live and when an official arrives on scene from Princeton Observatory, not to be confused with Princeton University Observatory, the reporter has to remind him a couple of times to get closer to the microphone. Small details that can sell the reality and naturalism of a thing.

The actor who played our brave reporter had studied the recordings of the Hiddenberg broadcast at the library of records and delivered an urgent and pressing performance to describe the odd sounds coming from the meteorite and general confusion from authorities and onlookers alike. A foley artist at CBS brought a rusty pickle jar to the microphone and slowly opened it and this was the sound of the spaceship opening. And as the ventriloquist act ended and the show entered a musical break, folks began channel surfing on the radio. And some stumbled upon an alien invasion happening here in the U.S. In New Jersey of all places.

This was a politically fraught moment in America as well, still recovering from The Great Depression and the first World War and on the precipice of the second, literally a year away. When people heard of alien invaders, they might think of fascist Germans or red Communists as readily as they might imagine little green men.

"I got the idea from a BBC show that had gone on the year before [sic] when a Catholic priest told how some Communists had seized London and a lot of people in London believed it. And I thought that'd be fun to do on a big scale, let's have it from outer space—that's how I got the idea." -Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles. HarperAudio, September 30, 1992

As the broadcast continued, listeners were told poison smoke was fumigating entire towns and the reports were often interrupted by fill-in piano as if something terrible was happening and that the producers needed to stall for time. And as Carl Phillips, our fictional reporter, you remember, observed the aliens using a heat gun against onlookers, his feed goes dead and stays silent for a sickening amount of time. He risked his life for us. He bore witness and reported the beginning of the end, and now he likely perished.

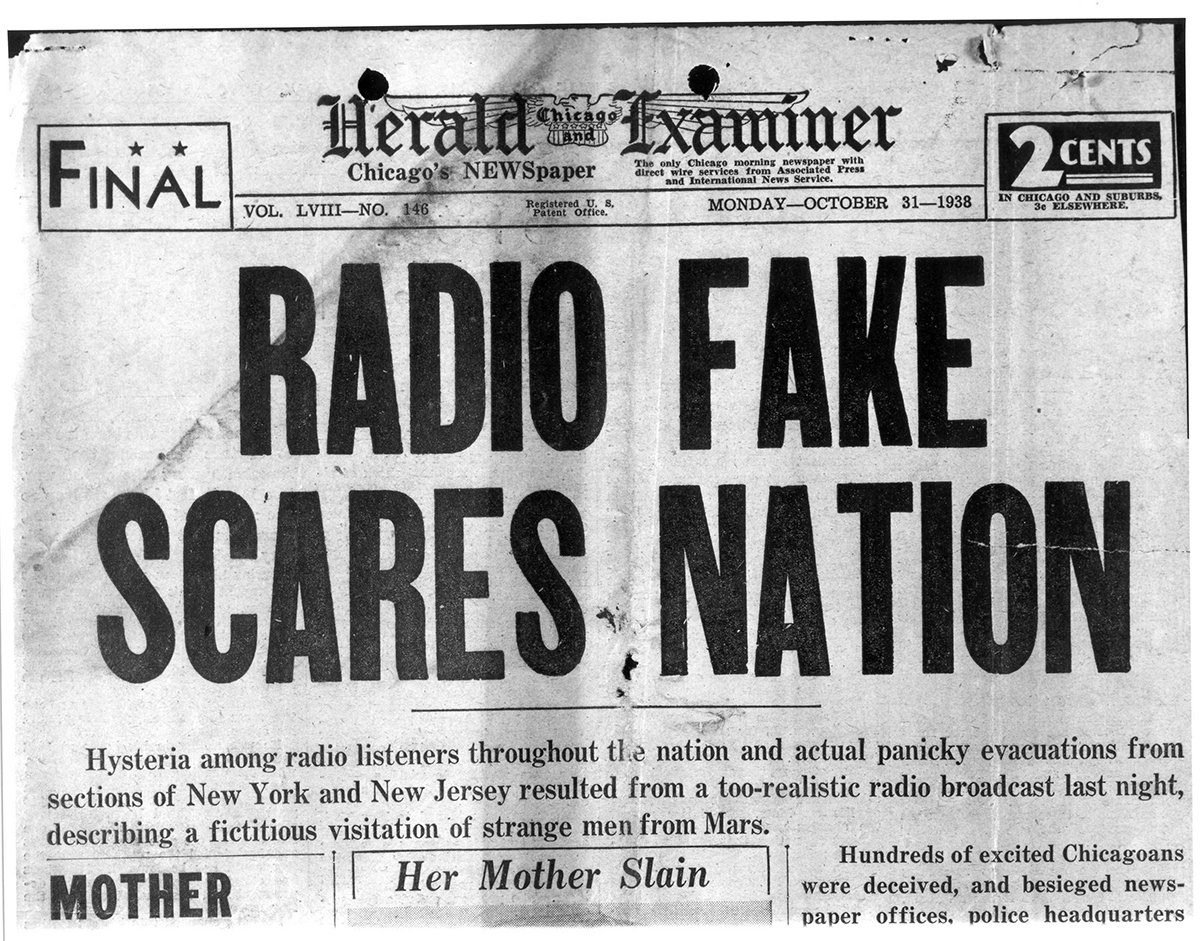

AT&T telephone operators reported that their call boards lit all the way up during the broadcast as people tried to ascertain the threat of what was happening. Reports of thousands of people running into the hills to hide permeated newspapers. The faint of heart was said to be checked in to hospitals and treated for shock. Young folk running home to rescue their families. Teams of alien hunters entering the area to find these invaders.

The police arrived outside the studios of CBS as the show was nearly complete. Welles reported that this was to protect the troupe from enraged listeners more so then to apprehend our young broadcasters. Then Welles took the stage to deliver a more conventional narrative as a survivor of the alien invasion, and like in the original novel, the threat is defeated mundanely by natural Earth microbes that the aliens were vulnerable to. Welles delivers his outro monologue, the show ends, and the music is cued.

"Our actual broadcasting time, from the first mention of the meteorites to the fall of New York City, was less than forty minutes. During that time, men travelled long distances, large bodies of troops were mobilized, cabinet meetings were held, savage battles fought on land and in the air. And millions of people accepted it—emotionally if not logically." -Houseman, John (1972) Run-Through: A Memoir

Another Kind of Theatre, Another Kind of Panic

The following day, Orson Welles, delivered a press conference. Surrounded by a gaggle of reporters who drilled in on Welles’ awareness of his effect, the choices to use the names of real places and the use of news conventions to create an air of authority. Close collaborators commented that that was as rattled as they had ever seen Welles, genuinely remorseful and apologetic. Welles said it was one of his best performances ever delivered. Newspapers around the country published his photo and his name and his company shortly before the opening night of his next play Danton’s Death. A play which unfortunately flopped, but that’s another story.

Part of what I want to argue here is that there is another theatre in this story. And another kind of panic broadcast.

Newspapers legitimized the panic, radio added to the discourse, a dialogue began and the broadcast industry was rattled. William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper tycoon that inspired Citizen Kane, urged broadcasters to self-police lest the FCC get involved, and questions of ethics, legislation and damages were posed to the industry and to Welles himself.

Ambivalent on the critical baggage the exposure brought, Welles embraced the story as part of his great myth and turned the notoriety into an asset. He was the man who scared America. And he chose to tell and reify the story many times afterward until the press, and Welles and spoken word cemented this story into the popular zeitgeist, so that even a contemporary lay person is likely to have heard about some silly people in New York,New Jersey and Missoula Montana who were afraid of aliens coming to Earth.

One researcher estimated that 6 million people listened to that broadcast. RadioLab suggested 12 million people heard it. A PBS documentary allowed that tens of millions of Americans were listening. And from that total, a significant fraction believed. A million or so Americans, ready for Martian conquest. It’s quite a thought. Quite an image. But the thing is, this isn’t true.

Modern media researchers are largely skeptical as to the scale of effect that The Panic Broadcast actually instilled in the hearts of Americans. There are no actual hospital records of people being checked in with shock. The stories of folks running to the hills are largely anecdotal. A survey of five thousand households by C.E. Hooper rating services suggested that from their poll, virtually nobody was listening.

Why inflate such a story?

“Blame America’s newspapers. Radio had siphoned off advertising revenue from print during the Depression, badly damaging the newspaper industry. So the papers seized the opportunity presented by Welles’ program to discredit radio as a source of news.” -Jefferson Pooley and Michael J. Socolow, Slate Oct 28, 2013

Welles had a theatre to sell. CBS had content to create and distribute. Newspapers had a competitor to slander. And Americans had an imagination to nourish. A predictable narrative feedback loop.

There were, indeed, large volumes of calls to authorities to figure out what was going on, which is a rather rational response to suss out the accuracy of the information they were consuming. And there are plenty of first hand accounts of people feeling thrilled and enjoying their suspension of disbelief, and those who were quite angry with having been tricked. And I’m sure there are plenty of logical folks who still felt that chilling fear when contemplating if an alien invasion is something one quickly needed to come to terms with. Human beings have had to integrate more absurd truths. And will again.

The Medium and the Magician

Part of why I love thinking about this story is because it raises so many questions for me. It makes me think of technology and the mediums we use to tell stories. It makes me think of the role of the story teller, and the responsibility of the story receiver.

What is our responsibility to engage, challenge and investigate absurd or unbelievable narratives? How do we navigate a fragmented and contradictory media landscape? How far do we stretch our imagination before we decided it’s time to take a nap or leave the grid?

Thinking about this I feel depressed at times, thinking at this moment there are thousands, maybe millions, of little panic broadcasts happening at any given time. Stories and narratives that incite a deep and motivating fear in the hearts of human beings. Perhaps it's a conspiracy theory, or misinformation or a flagrant lie. But then I think about children, and how they are always being introduced into the world, and I think about when we ourselves were coming up. We encountered many scary stories. A ghost story around a campfire is a little panic broadcast. Hearing a parent’s reprimanding voice is a kind of panic broadcast. And encountering fear then seems rather natural.

I was easy to scare as a child. Perhaps I still am. But I remember some movies, some stories, shook me to my core. I remember a classmate telling me about a show that was about a boy who died over and over again, and nobody knew why or acknowledged it. He wore an orange coat and nobody could see his face. That scared the shit out of me. I had nightmares about it. For weeks. They were describing Kenny from South Park.

Another time, my neighbor told me Chucky the killer doll was real and I stayed up in my treehouse until my dad came home.

Sometimes even just an irregular sound or a vague image in the dark was enough to terrify me in the dead of night.

Theatre of the imagination.

Similarly, movies like The Grudge or The Ring, I didn’t even watch them at the time, but I would see trailers, and the trailers were somehow worse. For me, scary movie trailers were like planting a scary seed. It lacked context, a beginning, an end, a resolution, a framework to understand it. And from that perspective, I can see how just tuning into the Panic Broadcast might be incredibly jarring.

I think that was a huge motivator for me to learn mediums. If I could identify the green screen, or see the special effect, if I could break down the form and understand it mechanically, then ghosts and demons and aliens wouldn’t have such a strong hold over me. Though maybe they still do to an extent.

I also think of shock as a political mechanism. Naomi Klein is author of a text called The Shock Doctrine which explores this idea of “disaster capitalism,” in which political actors and corporate interests take advantage of the wake that hurricanes, wars and tragedies leave behind to gain capital and dispossess average people. So for example, let’s say fires sweep through California, burning through neighborhoods and incinerating homes. Private land investors may offer displaced residents pennies on the dollars to purchase the land. Those people then have to make a quick decision to play the long game in rebuilding their homes, collecting on insurance or vetting a better offer, or take the deal to cover immediate expenses. So how do humans and societies behave in the face of zombie apocalypses and alien invasions?

A dozen movies and tv shows come to mind that explore this thought experiment, often times with the same Hobbesian cynicism that would have us believe that humans by default are naturally savage and cruel. Season after season of The Walking Dead subjecting us to our favorite characters getting offed leaving us emotionally drained or completely numb. It’s exhausting. Even in the War of the Worlds broadcast, Pierson, one of the sole survivors of the cosmic incursion, desperate to find another human being, only manages to find a crazed militaristic fascist who plans on taking over the Martian weapons to then take over the Martian fleet and by extension their domain over their human chattel slaves. And even the humans listening to the program are reported to have simply run for the hills, roam around with guns or simply succumb to an overloaded nervous system. I understand that there are limited responses when environmental pressures increase and creative avenues are fewer, but at least in the domain of fiction, let us imagine and envision another way.

I find that there’s an odd creative tension that comes from this media when it asks us to imagine a fantastical world full scifi gizmos, magic, shapeshifters and interplanetary travel, while simultaneously disallowing us to imagine alternative political futures. It feels to me an extension of what writer Mark Fisher calls “capitalist realism,” which describes a futility and inevitability of the status quo and current social arrangement to be the only feasible future. And the only thing that can disrupt the continuance of this thing is some sort of Martian heat ray or Earthly heat dome.

“Looking ahead to coming disasters, ecological and political, we often assume that we are all going to face them together - that what's needed are leaders who recognize the destructive course that were on, but I’m not so sure.

Perhaps part of the reason that so many of our elites, both political and corporate, are so sanguine about climate change is that they are confident that they will be able to buy their way out of the worst of it.

This may also partially explain why so many Bush supporters are Christian end-timers. It’s not just that they need to believe that there is an escape hatch from the world they are creating, its that the rapture is a parable for what they are building down here – a system that invites destruction and disaster then swoops in with private helicopters and airlifts them and their friends to divine safety.” -Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism

When I think of the mechanism that allowed some to believe not only that aliens were in New Jersey, but that they existed to begin with, the two things that come to mind are trust and imagination. People trusted the information that was being presented because they trusted a medium and industrial apparatus that held a great deal of authority, and their imagination allowed them to fill in the blanks from there. However, urgency and shock cripple possibility and put us in a survival state where flight-or-fight seem like the only options.

I think we are in a moment, an age, of shock and panic. And I feel that same fear I get when I don’t understand what’s happening. Shock and panic relies on disorientation. On overwhelming one. So I try to stay grounded, learn my history, understand what’s happening materially and work to understand reality, including of all of its absurdities, ambiguities, and ambivalent accounts. It’s slow work.

But working in this fear-stricken state is important, and we can learn to work through fear, the same way that we learn to work when we’re tired. And as we exercise our political imagination and dream of possible futures, a defiant act of science fiction in and of itself, we will add these as tools for when we do undergo true crisis, aliens or otherwise.

I like the story of The Panic Broadcast a lot. It’s a bit of a Russian doll. From it’s legendary reception. To Welles cleverly adapting it for Radio. To the original text himself, written by H.G. Welles, who himself was an ardent socialist who imagined benevolent futures. I find it compelling that human might wasn’t what ended the Martians, but rather something mundane, something unexpected, something small. A microbe. What a strange story.

The strangest thing about this story, though, is that they did land. Didn’t they? The aliens. They descended on Grover’s Mill that night in 1938. Right around 8pm. When their ship opened up it sounded like a rusty pickle jar lid turning about. And they’re still here. Among us now. Closer than we realize. And what are their intents I wonder. What do they want? What will they do next?

How wicked. Let me conclude by citing the end of that fateful recording for you:

“This is Orson Welles, ladies and gentlemen, out of character to assure you that The War of The Worlds has no further significance than as the holiday offering it was intended to be. The Mercury Theatre's own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying Boo! Starting now, we couldn't soap all your windows and steal all your garden gates by tomorrow night. . . so we did the best next thing. We annihilated the world before your very ears, and utterly destroyed the C. B. S. You will be relieved, I hope, to learn that we didn't mean it, and that both institutions are still open for business. So goodbye everybody, and remember the terrible lesson you learned tonight. That grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch, and if your doorbell rings and nobody's there, that was no Martian. . .it's Hallowe'en.” -War of the Worlds: Mercury Theatre on the Air (1938)